Each of Subversion's core libraries can be said to exist in one of three main layers—the Repository Layer, the Repository Access (RA) Layer, or the Client Layer (see Figure 1, “Subversion's Architecture”). We will examine these layers shortly, but first, let's briefly summarize Subversion's various libraries. For the sake of consistency, we will refer to the libraries by their extensionless Unix library names (libsvn_fs, libsvn_wc, mod_dav_svn, etc.).

- libsvn_client

Primary interface for client programs

- libsvn_delta

Tree and byte-stream differencing routines

- libsvn_diff

Contextual differencing and merging routines

- libsvn_fs

Filesystem commons and module loader

- libsvn_fs_base

The Berkeley DB filesystem back-end

- libsvn_fs_fs

The native filesystem (FSFS) back-end

- libsvn_ra

Repository Access commons and module loader

- libsvn_ra_dav

The WebDAV Repository Access module

- libsvn_ra_local

The local Repository Access module

- libsvn_ra_serf

Another (experimental) WebDAV Repository Access module

- libsvn_ra_svn

The custom protocol Repository Access module

- libsvn_repos

Repository interface

- libsvn_subr

Miscellaneous helpful subroutines

- libsvn_wc

The working copy management library

- mod_authz_svn

Apache authorization module for Subversion repositories access via WebDAV

- mod_dav_svn

Apache module for mapping WebDAV operations to Subversion ones

The fact that the word “miscellaneous” only appears once in the previous list is a good sign. The Subversion development team is serious about making sure that functionality lives in the right layer and libraries. Perhaps the greatest advantage of the modular design is its lack of complexity from a developer's point of view. As a developer, you can quickly formulate that kind of “big picture” that allows you to pinpoint the location of certain pieces of functionality with relative ease.

Another benefit of modularity is the ability to replace a given module with a whole new library that implements the same API without affecting the rest of the code base. In some sense, this happens within Subversion already. The libsvn_ra_dav, libsvn_ra_local, libsvn_ra_serf, and libsvn_ra_svn libraries each implement the same interface, all working as plugins to libsvn_ra. And all four communicate with the Repository Layer—libsvn_ra_local connects to the repository directly; the other three do so over a network. The libsvn_fs_base and libsvn_fs_fs libraries are another pair of libraries that implement the same functionality in different ways—both are plugins to the common libsvn_fs library.

The client itself also highlights the benefits of modularity in the Subversion design. Subversion's libsvn_client library is a one-stop shop for most of the functionality necessary for designing a working Subversion client (see the section called “Client Layer”). So while the Subversion distribution provides only the svn command-line client program, there are several third-party programs which provide various forms of graphical client UI. These GUIs use the same APIs that the stock command-line client does. This type of modularity has played a large role in the proliferation of available Subversion clients and IDE integrations and, by extension, to the tremendous adoption rate of Subversion itself.

When referring to Subversion's Repository Layer, we're generally talking about two basic concepts—the versioned filesystem implementation (accessed via libsvn_fs, and supported by its libsvn_fs_base and libsvn_fs_fs plugins), and the repository logic that wraps it (as implemented in libsvn_repos). These libraries provide the storage and reporting mechanisms for the various revisions of your version-controlled data. This layer is connected to the Client Layer via the Repository Access Layer, and is, from the perspective of the Subversion user, the stuff at the “other end of the line.”

The Subversion Filesystem is not a kernel-level filesystem that one would install in an operating system (like the Linux ext2 or NTFS), but a virtual filesystem. Rather than storing “files” and “directories” as real files and directories (as in, the kind you can navigate through using your favorite shell program), it uses one of two available abstract storage backends—either a Berkeley DB database environment, or a flat-file representation. (To learn more about the two repository back-ends, see the section called “Choosing a Data Store”.) There has even been considerable interest by the development community in giving future releases of Subversion the ability to use other back-end database systems, perhaps through a mechanism such as Open Database Connectivity (ODBC). In fact, Google did something similar to this before launching the Google Code Project Hosting service: they announced in mid-2006 that members of its Open Source team had written a new proprietary Subversion filesystem plugin which used their ultra-scalable Bigtable database for its storage.

The filesystem API exported by libsvn_fs contains the kinds of functionality you would expect from any other filesystem API—you can create and remove files and directories, copy and move them around, modify file contents, and so on. It also has features that are not quite as common, such as the ability to add, modify, and remove metadata (“properties”) on each file or directory. Furthermore, the Subversion Filesystem is a versioning filesystem, which means that as you make changes to your directory tree, Subversion remembers what your tree looked like before those changes. And before the previous changes. And the previous ones. And so on, all the way back through versioning time to (and just beyond) the moment you first started adding things to the filesystem.

All the modifications you make to your tree are done within the context of a Subversion commit transaction. The following is a simplified general routine for modifying your filesystem:

Begin a Subversion commit transaction.

Make your changes (adds, deletes, property modifications, etc.).

Commit your transaction.

Once you have committed your transaction, your filesystem modifications are permanently stored as historical artifacts. Each of these cycles generates a single new revision of your tree, and each revision is forever accessible as an immutable snapshot of “the way things were.”

Most of the functionality provided by the filesystem

interface deals with actions that occur on individual

filesystem paths. That is, from outside of the filesystem, the

primary mechanism for describing and accessing the individual

revisions of files and directories comes through the use of

path strings like /foo/bar, just as if

you were addressing files and directories through your

favorite shell program. You add new files and directories by

passing their paths-to-be to the right API functions. You

query for information about them by the same mechanism.

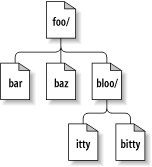

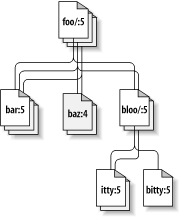

Unlike most filesystems, though, a path alone is not enough information to identify a file or directory in Subversion. Think of a directory tree as a two-dimensional system, where a node's siblings represent a sort of left-and-right motion, and descending into subdirectories a downward motion. Figure 8.1, “Files and directories in two dimensions” shows a typical representation of a tree as exactly that.

The difference here is that the Subversion filesystem has a

nifty third dimension that most filesystems do not

have—Time!

[53]

In the filesystem interface, nearly every function that has a

path argument also expects a

root argument. This

svn_fs_root_t argument describes

either a revision or a Subversion transaction (which is simply

a revision-in-the-making), and provides that third-dimensional

context needed to understand the difference between

/foo/bar in revision 32, and the same

path as it exists in revision 98. Figure 8.2, “Versioning time—the third dimension!” shows revision

history as an added dimension to the Subversion filesystem

universe.

As we mentioned earlier, the libsvn_fs API looks and feels like any other filesystem, except that it has this wonderful versioning capability. It was designed to be usable by any program interested in a versioning filesystem. Not coincidentally, Subversion itself is interested in that functionality. But while the filesystem API should be sufficient for basic file and directory versioning support, Subversion wants more—and that is where libsvn_repos comes in.

The Subversion repository library (libsvn_repos) sits (logically speaking) atop the libsvn_fs API, providing additional functionality beyond that of the underlying versioned filesystem logic. It does not completely wrap each and every filesystem function—only certain major steps in the general cycle of filesystem activity are wrapped by the repository interface. Some of these include the creation and commit of Subversion transactions, and the modification of revision properties. These particular events are wrapped by the repository layer because they have hooks associated with them. A repository hook system is not strictly related to implementing a versioning filesystem, so it lives in the repository wrapper library.

The hooks mechanism is but one of the reasons for the abstraction of a separate repository library from the rest of the filesystem code. The libsvn_repos API provides several other important utilities to Subversion. These include the abilities to:

create, open, destroy, and perform recovery steps on a Subversion repository and the filesystem included in that repository.

describe the differences between two filesystem trees.

query for the commit log messages associated with all (or some) of the revisions in which a set of files was modified in the filesystem.

generate a human-readable “dump” of the filesystem, a complete representation of the revisions in the filesystem.

parse that dump format, loading the dumped revisions into a different Subversion repository.

As Subversion continues to evolve, the repository library will grow with the filesystem library to offer increased functionality and configurable option support.

If the Subversion Repository Layer is at “the other end of the line”, the Repository Access (RA) Layer is the line itself. Charged with marshaling data between the client libraries and the repository, this layer includes the libsvn_ra module loader library, the RA modules themselves (which currently includes libsvn_ra_dav, libsvn_ra_local, libsvn_ra_serf, and libsvn_ra_svn), and any additional libraries needed by one or more of those RA modules (such as the mod_dav_svn Apache module or libsvn_ra_svn's server, svnserve).

Since Subversion uses URLs to identify its repository

resources, the protocol portion of the URL scheme (usually

file://, http://,

https://, svn://, or

svn+ssh://) is used to determine which RA

module will handle the communications. Each module registers

a list of the protocols it knows how to “speak”

so that the RA loader can, at runtime, determine which module

to use for the task at hand. You can determine which RA

modules are available to the Subversion command-line client,

and what protocols they claim to support, by running

svn --version:

$ svn --version svn, version 1.4.3 (r23084) compiled Jan 18 2007, 07:47:40 Copyright (C) 2000-2006 CollabNet. Subversion is open source software, see http://subversion.tigris.org/ This product includes software developed by CollabNet (http://www.Collab.Net/). The following repository access (RA) modules are available: * ra_dav : Module for accessing a repository via WebDAV (DeltaV) protocol. - handles 'http' scheme - handles 'https' scheme * ra_svn : Module for accessing a repository using the svn network protocol. - handles 'svn' scheme * ra_local : Module for accessing a repository on local disk. - handles 'file' scheme $

The public API exported by the RA Layer contains functionality necessary for sending and receiving versioned data to and from the repository. And each of the available RA plugins is able to perform that task using a specific protocol—libsvn_ra_dav speaks HTTP/WebDAV (optionally using SSL encryption) with an Apache HTTP Server that is running the mod_dav_svn Subversion server module; libsvn_ra_svn speaks a custom network protocol with the svnserve program; and so on.

And for those who wish to access a Subversion repository using still another protocol, that is precisely why the Repository Access Layer is modularized! Developers can simply write a new library that implements the RA interface on one side and communicates with the repository on the other. Your new library can use existing network protocols, or you can invent your own. You could use inter-process communication (IPC) calls, or—let's get crazy, shall we?—you could even implement an email-based protocol. Subversion supplies the APIs; you supply the creativity.

On the client side, the Subversion working copy is where all the action takes place. The bulk of functionality implemented by the client-side libraries exists for the sole purpose of managing working copies—directories full of files and other subdirectories which serve as a sort of local, editable “reflection” of one or more repository locations—and propagating changes to and from the Repository Access layer.

Subversion's working copy library, libsvn_wc, is directly

responsible for managing the data in the working copies. To

accomplish this, the library stores administrative information

about each working copy directory within a special

subdirectory. This subdirectory, named

.svn, is present in each working copy

directory and contains various other files and directories

which record state and provide a private workspace for

administrative action. For those familiar with CVS, this

.svn subdirectory is similar in purpose

to the CVS administrative directories

found in CVS working copies. For more information about the

.svn administrative area, see the section called “Inside the Working Copy Administration Area”in this chapter.

The Subversion client library, libsvn_client, has the

broadest responsibility; its job is to mingle the

functionality of the working copy library with that of the

Repository Access Layer, and then to provide the highest-level

API to any application that wishes to perform general revision

control actions. For example, the function

svn_client_checkout() takes a URL as an

argument. It passes this URL to the RA layer and opens an

authenticated session with a particular repository. It then

asks the repository for a certain tree, and sends this tree

into the working copy library, which then writes a full

working copy to disk (.svn directories

and all).

The client library is designed to be used by any

application. While the Subversion source code includes a

standard command-line client, it should be very easy to write

any number of GUI clients on top of the client library. New

GUIs (or any new client, really) for Subversion need not be

clunky wrappers around the included command-line

client—they have full access via the libsvn_client API

to same functionality, data, and callback mechanisms that the

command-line client uses. In fact, the Subversion source code

tree contains a small C program (which can be found at

tools/examples/minimal_client.c that

exemplifies how to wield the Subversion API to create a simple

client program

[53] We understand that this may come as a shock to sci-fi fans who have long been under the impression that Time was actually the fourth dimension, and we apologize for any emotional trauma induced by our assertion of a different theory.